I’m a venture capitalist. My job is to find new, undersaturated talent markets and to invest in those before they even know they are venture-scalable. Content and Creators are what I’m betting on. They are my two loves.

Over the last five years, I’ve been watching billions of dollars being thrown to what can only be described as the “creator economy” and it’s clear that most of those bills were set on fire. I don’t want to blame anyone for that - since “Creator” is something so misunderstood that we can’t even decide on its definition or who is/isn’t one.

Creator is a $200B industry. Creators are rich. Creators need this product.

All assumptions. I’ve invested 1) with, 2) for, and 3) in Creators, professionally. I guarantee that there are maybe four or five investors on the planet that can say that. My biggest takeaway is this: The Creator ecosystem is an underdeveloped ecosystem. It’s been entirely misunderstood and hasn’t matured.

I started this newsletter is to continue to find out why.

The popular claim that “the internet democratized content” usually bundles together at least three different propositions: (a) production is cheap enough for many people to participate, (b) publishing is open enough that gatekeeping is minimal, and (c) distribution is technically global, so the market behaves like an open competitive arena. Those first two propositions are often true in a narrow, technological sense. The third, about market structure and competitive outcomes, does not automatically follow.

Economists typically evaluate whether an arena is “free” by looking less at whether participation is allowed and more at how allocation works and what outcomes that allocation produces. Perfect competition is the usual baseline model: many buyers and sellers, free entry and exit, and “all relevant information” available to market participants (meaning: no systematic information advantage that changes who wins).

I support platforms as key components to online US GDP, creators of new jobs and markets and the likes of which any open capitalist would support the hand that feeds them. I also want to know how as said capitalist, I have an understanding of how the economy works.

In microeconomic theory, markets are evaluated based on structure and tested with real-world outcomes. A market may allow participation while still exhibiting structural constraints that meaningfully shape competitive outcomes. Therefore, before assessing whether the content economy is “free,” we must first define what freedom means within economic analysis.

The Distinction Between Production Freedom and Market Freedom

This starts from a simple conversation with an institutional LP with enough traditional financial education that reasoned exploring investing in Creators as firms, or at least Channels as Cash-Flow Portfolios. The conversation flowed as follows: “The content economy clearly exhibits production freedom. Barriers to uploading content are minimal. Equipment costs are historically low. Platform access is global.”

For this reason, while typically exciting for me, they had interest in buying up specific channels of which, at that moment of time, were performing well for the expectation he had at the moment. I had been instructed to help their analysts learn models that I had been working on to prove a perfect, juicy monopolistic outcome because of the health of the current business. Still, something didn’t sit right. I had been in enough pro-Creator or at least enough pro-Creator-Capitalist group chats to know that there is still some insider-baseball to be played. There is some arbitrage to be found separate from perfect content execution. Simply put, great content businesses do not grow on healthy vines. Production freedom does not automatically imply competitive freedom.

I decided to run through why these businesses or channels die and what the definition of that can mean if the content itself is truly scalable and yield-yummy without constant production of new units of content.

In many markets, firms can produce freely but cannot access customers without intermediaries controlling distribution channels. Economic history offers parallels: railroads, telecommunications, broadcast spectrum, and energy infrastructure have all functioned as distribution bottlenecks. In each case, production was decentralized while access to consumers was mediated through controlled infrastructure.

In traditional businesses and markets, the scarcity lies in tandem with production (or in this case, creation). In digital content markets, the scarce resource is the ability to secure attention.

Attention scarcity transforms distribution into the primary economic constraint. Once attention becomes scarce, coordination mechanisms must allocate it. On modern platforms, that allocation is governed by algorithmic ranking systems.

I cannot stress enough: the presence of ranking is not itself problematic. Ranking is a necessary response to scarcity. The question is whether the ranking mechanism preserves competitive neutrality or embeds structural asymmetry.

What Economists Mean by a Free Market

In classical and neoclassical frameworks, a free market is defined by decentralized exchange under conditions where no single actor exerts coercive control over participation or price formation. More specifically, economic freedom tends to rely on several structural conditions:

Low barriers to entry and exit. New firms can compete without prohibitive capital requirements, regulatory hurdles, or control over essential infrastructure.

Diffuse market power. No single firm can meaningfully influence price or suppress competitors.

Information symmetry. Participants possess adequate information to respond rationally to incentives.

Competitive mobility. Firms can scale or decline based on performance rather than structural exclusion.

Decentralized coordination. Market outcomes emerge from distributed decision-making rather than centralized allocation.

The benchmark model of perfect competition, as formalized in Marshallian and later neoclassical frameworks, functions as a comparative baseline. Today, we are going to access the content ecosystem by these similar benchmarks.

There is a reality to a test like this: markets that deviate from these criteria may still be dynamic and innovative. They may still be productive, but they are no longer structurally free in the classical sense.

Information Symmetry and the Hayekian Problem

One of the strongest theoretical defenses of free markets has been articulated by Friedrich Hayek: decentralized price systems efficiently aggregate dispersed information. In competitive markets, price signals coordinate behavior without central planning. In content markets, however, the primary coordination mechanism is not direct price, but attention-distributed ranking.

Creators, however, do not receive a transparent price signal for distribution. (They receive exposure based on opaque weighting systems. The exposure, of course, has an ever-changing price (CPM) determined by ad-interest, conversion metrics, and overall the Ads department of a major platform. That, however, is not the primary metric we’re looking at.)

The informational feedback loop is partially hidden. This introduces a very critical question: if market participants cannot fully observe the rules governing distribution, can the system be considered informationally symmetric?

Information asymmetry is one of the canonical sources of market distortion in traditional microeconomic theory. When one side of a market possesses materially superior knowledge about the allocation mechanism, competitive conditions shift. For accuracy and probably legal purposes, I’m not going to say that certain creators are given this information with platform-malicious intent. I will say that there hasn’t been a strong challenge on how information symmetry strengthens the importance of not only Creators, but platforms in serious economic consideration.

Put simply: In the content economy, platforms possess complete visibility into ranking mechanics. Creators do not. This asymmetry probably does complicate the claim of market freedom.

Who cares?

The central issue is not whether platforms allow participation. They really do. It seems like the logic is simple, well communicated and understood. Content creator = good. More content = good. Platform = money.

The issue is whether access to meaningful distribution and yield [which would sound like sustained visibility capable of generating economic return] is competitively accessible under transparent and symmetric conditions.

In other words: Are creators price-takers in an open competitive environment or are they participants in a mediated system where infrastructure owners accidentally force-shape exposure?

If production is open but distribution is structurally intermediated, then the content economy may resemble a more platform-coordinated market rather than a frictionless competitive one.

So other than for investment purposes, why are we supposed to care?

As someone who works on, yes, investments but also policy and research about whatever content or creator world you think of while clicking on this, the market classification directly influences both interpretation and policy. Part of the reason why C-CPAR started was for all of this.

There is something very much so good that is happening within the platform ecosystem for people, money, and policy. And, if it helps them, a market characterized by diffuse competition and transparency requires minimal intervention. A market characterized by concentration and structural asymmetry invites different full-stack treatment altogether.

So now, we’re going to operationalize the criteria of market freedom and test them against observable characteristics of the content economy: concentration ratios, entry mobility, informational transparency, and structural advantage.

Two Levels of Competition in the Content Economy

For a moment, let’s consider all individual units of content that can be accessed individually. Oftentimes, when we think about the general creator economy, the personality and story and production stays at the forefront. But if we can consider a flat-base portfolio that accesses an interchangeable definition of “unit of content,” we can start seeing how the content economy works, rather than the individual mechanics of each platform. If the content economy is to be evaluated as one solid market, it must be evaluated using the same structural criteria economists use to define markets elsewhere.

Market freedom typically is assessed through observable features: concentration ratios, entry costs, information symmetry, and pricing power. So we’re going to try our best to see how the content economy matches up.

One reason the debate around whether the content economy is “free” feels muddled is that we often collapse two very different layers of competition into one. But they are actually not the same.

The creator economy operates on two overlapping competitive planes:

Unit-level competition. Where individual pieces of content compete for exposure.

Firm-level accumulation. Where exposure aggregates into durable scale and economic leverage.

Unit-Level Competition

Preface: For a moment, let’s consider all individual units of content that can be accessed individually. Oftentimes, when we think about the general creator economy, the personality and story and production stays at the forefront. But if we can consider a flat-base portfolio that accesses an interchangeable definition of “unit of content,” we can start seeing how the content economy works, rather than the individual mechanics of each platform.

If the content economy is to be evaluated as one solid market, it must be evaluated using the same structural criteria economists use to define markets elsewhere. Market freedom typically is assessed through observable features: concentration ratios, entry costs, information symmetry, and pricing power. So we’re going to try our best to see how the content economy matches up. ———

At the most immediate level, competition in the content or creator economy occurs at the level of the individual content unit. Whether a video, a post, a podcast episode: each individual unit enters the allocation system independently. Platforms do not (in most cases) allocate exposure based purely on who the creator is. They allocate exposure based on how the individual piece of content performs.

Ranking systems ingest behavioral signals: click-through rate, watch time, completion rate, engagement, session continuation. Behavioral signals determine how widely that specific unit of content is distributed. Note: User preference is … like you… believe it or not…multidimensional. It includes long-term trust, reputation, intellectual depth, community belonging. Ranking systems typically optimize for signals that are measurable at scale and in real time, creating a a measurement constraint.

Hal Varian and others writing on information goods have long noted that digital markets are governed by ranking and filtering mechanisms because information overload must be resolved algorithmically.1

In this sense, competition is very granular; making each upload is a new trial and each piece of content would have a probability of exposure conditional on performance.

Formally, we can think of exposure at time (t) as:

Eᵢ,ₜ = f(Qᵢ,ₜ)

Where Q represents performance metrics observable to the platform. A creator with 500 subscribers can have a video outperform a creator with 5 million, if the content generates stronger engagement signals. Small accounts can go viral and new entrants can break through. Legacy status does not guarantee distribution of a weak upload.

More importantly, on a per-video basis, the allocation system resembles competitive sorting rather than centralized assignment. Content competes on measurable performance. And, suure, if we were to stop here, the content economy sounds open: each product competes, consumer behavior determines amplification, and firms must respond to demand signals.

Firm-Level Accumulation

The system does not reset to zero after each upload. Instead, it makes exposure accumulate.

A creator who receives 100,000 impressions on one video does not return to a neutral baseline for the next. They retain (again, this varies per platform, but let’s assume one whole market for a minute) some fraction of that exposure in the from of subscribers, recognition, familiarity (brand), and algorithmic history. Over time, these accumulated exposures begin to function as economic capital.

Aaand now we get to the second later. While individual pieces of content compete at the unit level, exposure aggregates at the firm level. And once aggregated, that exposure can influence future allocation probabilities.

In its simplest form, unit-level exposure might look like this:

Eunit = f(Qunit, t)

Where exposure for content unit i at time t depends only on the quality or performance metrics of that unit. But in reality, exposure may look more like this:

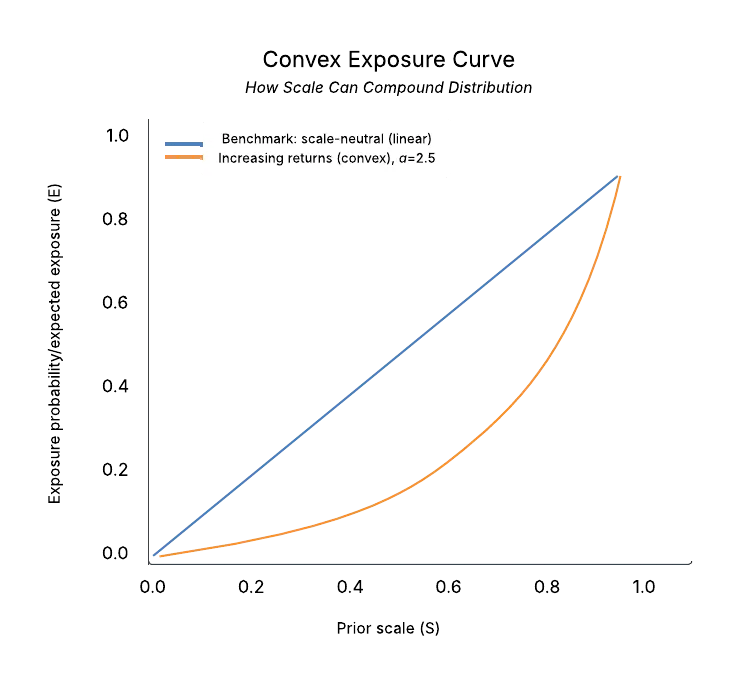

Ei,t = f(Qi,t,Sc,t-1)

Where Sc,t−1 represents the prior scale of Creator C.

Scale here means: subscriber base, historical watch time, past engagement rates, brand recognition, data sophistication, cross-platform spillover, and production capital.

Fig 1. The top row represents unit-level competition. The bottom box represents accumulated firm-level scale. The feedback arrow illustrates the structural condition under which prior exposure influences future exposure probability. This is the compounding mechanism.

HARD IF, if prior scale influences current exposure probability, even marginally, then competition itself shifts from purely trial-based sorting to path-dependent accumulation.

There is still potential to invest in creators that have moat. They can have the following, as either firms or founders, no matter what your definition preference can be. (I know we haven’t gone over Creators as Firms formally yet here, so just throwing it out there.)

A “Moat” as a creator can be the following: higher initial impression allotments, faster engagement sampling, greater click probability due to brand familiarity, higher advertiser demand, stronger cross-platform spillover, etc. Over time, of course, exposure converts into durable economics leverage, also referred to as momentum. This is where the content economy begins to resemble other attention markets (music streaming, publishing, venture capital) where outcomes follow a power-law distribution.

In short: Unit-level → Firm-level → Compounding → Structural question → Transition to concentration.

If individual pieces of content compete on measurable performance, the system may appear meritocratic. Sure, a strong upload can outperform a weak one, even regardless of creator size. But there are thousands of examples of small accounts can still break through. The presence of unit-level competition does not automatically guarantee firm-level contestability.

The structural question is this: Does unit-level meritocracy translate into firm-level mobility? In other words, even if each piece of content is evaluated independently, does the accumulation of exposure over time create actual durable advantages that are difficult to displace?

If exposure at time t depends only on current performance Q{i,t}, then competition remains unit-based and contestable. But if exposure at time ttt depends partially on prior scale S, then outcomes become path-dependent.

Path dependence means that early advantages (whether from timing, format, luck, or initial amplification) can compound. A creator who achieves scale gains structural benefits:

Higher baseline click probability due to familiarity

Larger initial sampling pools from subscribers

Greater advertiser demand

Stronger cross-platform spillover

Capital to invest in production and optimization

These emerge naturally from scale. If upward mobility is frequent and rapid, then concentration can reflect ongoing competition. And, if upward mobility is rare and incumbency persists, then firm-level compounding begins to resemble increasing returns markets; industries where early scale advantages dominate long-run outcomes.

And I know everyone is going to think this sounds like complaining or whining, but actually it’s a moment of clarity we have to have with ourselves on how pure of a market a capitalist is playing if given the cards to do so. If you can take anything away from here, it should be: there is still arbitrage within the creator ecosystem, either in talent or information, or preference, or anything that would require for one to be informed on how to play it.

From Compounding to Concentration

The Wrong Denominator

I’ve heard a lot of numbers trying to quantify the creator and content economy. $250B, $300B, or even half a trillion. Regardless of whatever shiny number can show how impactful or large, I know using ecosystem valuation as the denominator when discussing income concentration is a category error. We should focus on total creator or unit of content income.

In industrial organization, defining the market incorrectly produces distorted conclusions. A firm that appears small relative to the entire economy may be dominant within its actual competitive market. By this, if the top 1% of creators capture 25–30% of total creator income, that is economically meaningful; even if it represents a tiny fraction of total social media advertising spend.

The structure of competition must be evaluated at the level where firms actually compete: in exposure and revenue.

Modeling Creator Income Distribution

If firm-level compounding exists, we should expect to see it reflected in income distribution. Headlines cite figures like “the creator economy is worth $250 billion,” and from that conclude the market must be diffuse. The truth is that the majority of this data is not clean, non-biased or large enough to really evaluate. If you’d like to work on something here, send me an email.

But from what we have, the $250 billion figure includes: platforms, agencies, software providers, creator tooling, marketing infra, and ad intermediaries.

Across multiple reports suggests a few consistent facts:

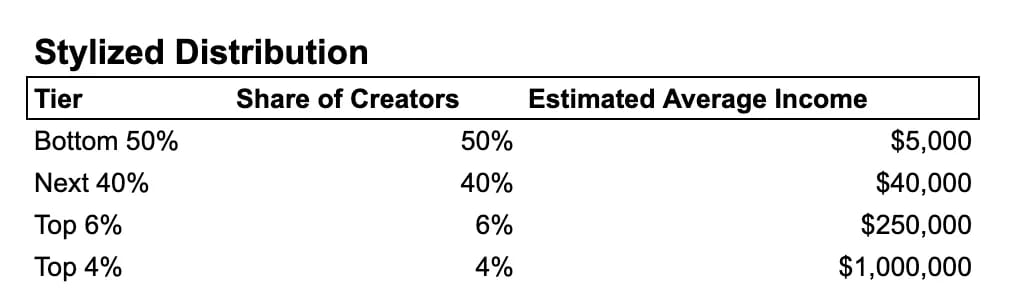

I know what you might think, those numbers alone imply skew. A market where the median is $15,000, but a visible subset earns millions is not symmetrically distributed. To estimate concentration meaningfully, we need to approximate total creator earnings and distribution tiers. Again, I cannot stress enough that this is using non live-time data and the data given to us. So we’re going to build a conservative model.

Let’s attempt a model

Assume roughly 2 million actively monetizing creators globally. That figure is debatable, but it provides a working scale. Now divide income into tiers consistent with survey medians and observed earnings dispersion:

Again, this is assuming a lot, so !Illustrative!, but it’s a solid attempt to understand distribution.

Heavy-tailed income distributions require increasing returns. In markets where distribution scales at near-zero marginal cost, small differences in exposure can translate into large differences in income. Sherwin Rosen’s “Economics of Superstars” demonstrated this dynamic decades ago: when one performer can reach millions at little additional cost, even modest differences in perceived quality generate disproportionate earnings dispersion.

Fig.2 The straight line represents a scale-neutral system: prior scale increases exposure proportionally. In such a system, doubling your size doubles your exposure.

What we do not know is whether prior scale materially influences exposure probability. If it does…then firm-level outcomes become path-dependent.

This could sound like bad news, but surprise surprise it is good news for a capitalist. There’s a shape of a power-law! It resembles the distributions observed in other increasing-returns markets (venture capital, book publishing, music streaming) where small differences in visibility compound over time.

Question still stands: Do new creators regularly enter the upper percentiles? Does turnover occur within the top income tiers? Or does scale harden into durable advantage?

If firm-level compounding exists, we should expect income concentration. But the question still stands as to why? And to answer that, we have to examine how per unit and per firm distribution actually works.

1 Hal R. Varian, “Markets for Information Goods,” 1998; related work on search and ranking in digital markets.

2 Linktree, https://linktr.ee/creator-report/

Thank you for taking the time out to read this. REPLY to this email to let me know what you think about this piece OR feel free to find me on X.

— Em.